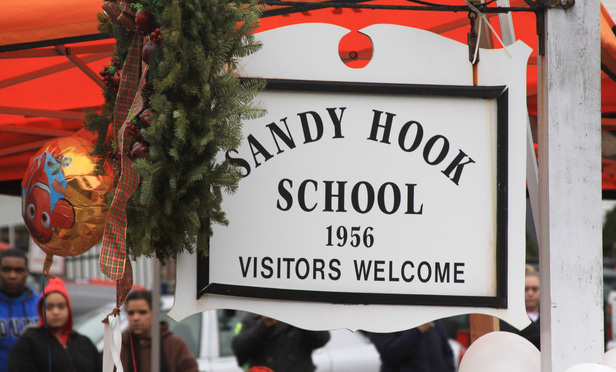

Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut

Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut

As the Connecticut Supreme Court is expected to begin later this year to hear an appeal from several families whose loved ones were killed in the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School massacre and who are seeking to hold manufacturers of the gun used responsible, legal experts, attorneys and law professors say the plaintiffs have a long, uphill battle.

The primary hurdle can only be cleared if the state’s high court rules that gun manufacturers bear responsibility under the theory of “negligent entrustment.” Such a ruling would require the court to overrule Fairfield District Superior Court Judge Barbara Bellis, who in granting motions from two gun manufacturers dismissing the complaint in October, wrote the law broadly prohibits lawsuits against gun makers, distributors, dealers and importers from harm caused by the criminal misuse of their firearms.

“The allegations in the present case do not fit within the common-law tort of negligent entrustment under well-established Connecticut law, nor do they come within (the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act)’s (PLCAA) definition of negligent entrustment,” Bellis wrote.

Many legal experts, while sympathetic to the families of the 20 children and six educators murdered by Adam Lanza, say many factors will need to fall into place in this first-impression case facing the high court for plaintiffs to prevail.

“It’s a novel creative long-shot legal theory,” said John Thomas, professor of law at Hamden-based Quinnipiac University. Thomas predicts a “unanimous decision” on behalf of the gun manufacturers, saying, “Some justices might not be happy about voting that way, but they will do so because the laws is so clear.”

Similarly, Sachin S. Pandya, professor of law at the University of Connecticut Law School in Hartford, said the plaintiffs attorney, led by Joshua Koskoff of the Bridgeport-based law firm of Koskoff Koskoff & Bieder, “are using negligent entrustment in a nontypical fashion. They are asking the court to innovate.”

Late last year, the state’s high court bypassed a lower court to hear the appeal, a decision hailed as a victory by attorneys representing the families. The court’s decision came only two weeks after nine families of the victims and a survivor appealed Bellis’ ruling, which many have said was a thoughtful and well-balanced decision.

“Judge Bellis’ decision was extremely supported by research and was well-reasoned. It was a scholarly opinion,” said Patrick Tomasiewicz, an adjunct paralegal studies professor at the University of Hartford in West Hartford and a partner in the Hartford law firm of Fazzano and Tomasiewicz.

According to Thomas, negligent entrustment “occurs when one party provides a product to another party while knowing that the receiving party is likely to cause someone an injury with the product. The key is that the entrustor knows, or reasonably should know, of the risk that the entrustee poses.”

The most oft-quoted ruling by the Connecticut Supreme Court dealing with negligent entrustment comes from a case involving an automobile in Greeley v. Cunningham in 1933. In that case, the high court, in overturning a lower trial court, wrote, “When the evidence proves that the owner of an automobile knows or ought reasonably to know that one to whom he entrusts it is so incompetent to operate it upon the highways that the former ought reasonably to anticipate the likelihood of injury to others by reason of that incompetence and such incompetence does result in such injury, a basis of recovery by the person injured is established.”

In interviews with the Connecticut Law Tribune, legal experts say negligent entrustment relating to an automobile is one thing but trying to transfer that to a gun used in a murder is another case, especially if there are many layers involved in how that weapon was purchased. “If you give a loaded gun to a 5-year-old, obviously that fits the definition [of negligent entrustment],” said Kenneth Bartschi, a partner in the Hartford-based law firm of Horton, Shields & Knox. “Nancy Lanza [Adam's mother and owner of the weapon in question] could have also been held liable [but she was killed by her son]. But the further you get from her, the more difficult negligent entrustment is to prove. It’s too far down the road and there are too many layers to know that [Adam Lanza] would do what he did. It’s one thing if the store owner does or does not do a background check and then sells to the gun owner.”

Lanza used a Remington Bushmaster AR-15 rifle in his shooting spree four years ago. The plaintiffs allege Remington sold the weapon to the distributor, Camfour, which in turn sold the rifle to the gun shop, Riverview Sales, which then sold the gun to Lanza’s mother. Remington, Bushmaster, Camfour and Riverview (which has since gone out of business) are all listed as defendants.

If the plaintiffs are to win in the Connecticut Supreme Court, the court will not have to only overrule Bellis and find negligent entrustment applicable, but must also square such a finding with the PLCAA, a federal law passed in 2005.

“After PLCAA was passed, the [National Rifle Association (NRA)] thanked President [George W.] Bush for signing the legislation,” Tomasiewicz said Monday. “It appears that Congress sought to pre-empt lawsuits by victims such as the Sandy Hook families.” The law, legal scholars say, pretty much gives immunity to gun manufacturers when being sued by plaintiffs such as those in the Sandy Hook case.

“I think it is a travesty to give gun manufacturers a legal immunity that is not available to any other manufacturer of any other product. It’s unfair to me,” Thomas said.

The question in the Connecticut case is whether a negligent entrustment theory of liability could prove an exception to the PLCAA.

Many experts who spoke to the Connecticut Law Tribune say the case is likely to be closely watched not only by the NRA and gun manufacturers but also attorneys and judges across the country.

“I think a lot of different groups are watching this case,” Pandya said. “They are doing so not necessarily because they have a deep interest in Connecticut common law, but because groups in different states [under PLCAA] are all subject to the gun immunity statute to which negligent entrustment could be the exception.”

Bartschi said that, depending on how the justices rule, the state high court might not be the last word on the negligent entrustment theory or its pre-emption by federal law.

“If the defendants win on state law grounds, it is over. That is it,” Bartschi said. “But if the court analyzes it on federal statute, the U.S. Supreme Court could take the case if they wanted to.”

How will the seven-member court rule? Gov. Dannel P. Malloy, a liberal Democrat, has a chance to replace Justice Peter T. Zarella, arguably the court’s must conservative justice, who left the bench at the end of December. In addition, Justice Dennis Eveleigh must retire in early October when he turns 70 years old. According to Tomasiewicz, the case might not be heard until after Eveleigh leaves the bench. “It could take six to nine months or longer” before the high court hears the case, he said. While Zarella was the most conservative justice along with Carmen Espinosa, the liberal wing, legal experts say, is led by Justices Richard Palmer and Andrew McDonald.

“I’m not even sure that the Zarella successor will be able to change the outcome,” said Tomasiewicz, adding, “It’s an uphill battle [for the plaintiffs]. No one has a crystal ball, but it will be a very difficult case for them to prevail.”

“I would not be surprised if the Connecticut Supreme Court were divided,” Bartschi said. “There are certainly different views there on how broad tort law should be in the court.”

Copyright Connecticut Law Journal. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed.

Robert Storace can be reached at 860 757-6642 or at [email protected].